|

|

|

|

|

|

|

SECTION 11 THE NORTH AMERICAN ARCTIC ARCHIPELAGO DISCOVERED & the N.W. PASSAGE REVEALED

WILLIAM EDWARD PARRY- FIRST OVERALL ARCTIC COMMAND 1819-20*

William Edward Parry (1790 -1855) knighted 1829, Rear Admiral Hydrographer to the Navy (1825-29), Lieutenant-Governor of Greenwich Hospital and accomplished violinist, was a son of a prominent family of the glorious city of Bath. After joining the Navy at thirteen, it was however as a young Lieutenant of 28 years that he first rose to prominence as the Royal Navy’s ‘blue-eyed boy’. Upon his return from Ross’s 1818 voyage as commander of the ‘Alexander’. (see section 10) Parry's obvious ability, coupled with his reasons for disagreement with Ross regarding the possibility of a North West Passage through Lancaster Sound, had impressed the Admiralty Board sufficiently for them to give him command of his own naval exploring expedition.

To give his voyage of discovery some historical context. In the same year Mary Shelly published the novel ‘Frankenstein’ and the 49th. parallel was established as being the frontier between British Canada and the US.

Parry left London 12 May 1819, in command of the barque-rigged 375-ton bomb-ketch ‘H.M.S. Hecla’ (built North Barton, 1815) and was accompanied by his long time friend, Lt. Matthew John Liddon in the 180-ton gun-brig ‘H.M.S. Griper’. The ships were true ice breakers, clad with 3-inch (7.6 cm) oak, reinforced with iron plates on their bows and internal cross-beams. The Griper turned out to be a poor sailor, slow and wallowing, a vessel not suited to voyages of exploration. The crew (combined total of 94 souls) was probably the youngest ever assembled for an Arctic voyage, the average age being 25. Among its members were Capt. E. Sabine, F.W. Beechey, J. Bushnan and J.C. Ross. As an incentive every crewmember was on double pay and supplied with a wolf skin blanket.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

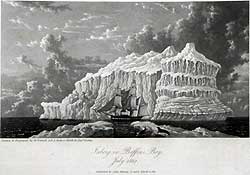

Parry was an ideal choice as an expedition commander, for he possessed not only all the virtues of a good officer, but also an inquiring mind, a capacity to adapt to circumstances and a flair for innovation that was positively creative. He followed Ross’s route along the Greenland coast. Then, after two attempts, Parry succeeded in cutting and warping directly through the pack ice of Baffin Bay to Lancaster Sound. This considerable accomplishment placed him a month ahead of Ross’s position in the previous year, despite the fact that Parry had started a fortnight later. Parry admitted that the knowledge he had gained of the open water on the west side of Baffin Bay from Ross’s voyage was invaluable. Finding the sound clear of ice, the two ships sped westward until spotting a heavy ice barrier across Barrow Strait at Maxwell Bay. They then turned south to explore Prince Regent Inlet, dropping sealed bottles overboard every day, containing information on their position and progress.

Upon turning north again and finding a passage through the ice barrier of Barrow Strait, they proceeded west passing the Magnetic North Pole. They discovered and named Devon, Cornwallis, Bathurst, Byam Martin and Melville Islands, covering a distance of over 30° of longitude, mapping and surveying as they went. The work formed the base of the future Arctic Geodetic Survey Network and represents a remarkable achievement under extremely difficult conditions.

In 1818 a King’s Order in Council reiterated the prize of £20,000 instigated by Dobbs in 1743 (see Sect 1 Prologue) for the discovery of a Northwest passage. In addition, a scale of prizes was set up for the attainment of various degrees of latitude north of the Arctic circle - an inducement that created a lively interest in Arctic exploration. On 6 September 1819, Parry crossed 110° W. of Greenwich in 74° 44’20” N. and so laid claim to a prize £5,000, he named the location Cape Bounty. His ships reached 112°51’W. before heavy ice forced them back to seek anchorage for the winter in Winter Harbour within ‘Hecla and Griper Bay’.

Parry had planned carefully for their long winter sojourn (26 September 1819 to 1 August 1820), the first such arctic wintering by an expedition. A weatherproof shelter was constructed over the dismasted decks and heating and ventilation pipes were installed. A strict diet and a system of medical inspection were enforced; bakery and brewery were established, as well as the distinguished Capt. Sabine's observation hut on shore. To combat the tedium of their enforced stay, a newspaper the North Georgia Gazette (edited by Sabine) was created, plays were performed and a regular exercise program was implemented. Very much the British public school attitude was fostered: indeed, this was the dictum of empire building put into practice. With the coming of spring, their supply of "Donkin’s Bully Beef"* could be supplemented with fresh game and meat. Scurvy was overcome, only one crew member succumbing to illness.

*Invented in 1817 the technology of preservation of provisions in cans was so new that the expedition was not supplied with, yet to be invented, can openers.

June 1-15, 1820 a 12 man shore party made an exploratory expedition across Dundas Peninsula, pushing some of their supplies in a handcart, the tracks of which were still visible 30 years later. They sighted Sabine Peninsula and returned without misadventure. The ships meanwhile had been prepared for departure, although the ice held them beset until 1 August. After that date they attempted to continue up what was to become known as McClure Strait; however, a mass of thick heavy pack ice blocked westward progress past 113°61’43.5”W. - further west than any previous navigator. As Scoresby had predicted, this voyage of discovery did indeed have great luck with the weather, for given the vagaries of arctic winters, Parry’s navigational distance achievements were not equaled for over thirty years. The expedition returned safely to Scotland on 1 and 3 November 1820, the ships having separated in a storm, carrying with them much useful information, observations, charts and specimens. The voyage made Parry a hero in England, where he was promoted to commander, received many awards and was elected to the Royal Society.

Parry had come within 13° of sailing through the long-sought North West Passage and his name is rightly immortalized in the group of islands he discovered. Today his name is just as synonymous with the Arctic as Cook’s is with the Pacific, for Parry had charted more unknown coastline than anyone since. But even more significant than his outstanding navigational triumph was the considerable experience gained, and noted in his fascinating account of the voyage, of how to survive the intense cold, isolation and boredom of an Arctic winter. Indeed, it was a mark of his considerable authority that not only was he, as leader, able to participate in the plays performed in front of the whole crew, but that their welfare and strict discipline were maintained by only having to resort to the lash once in the entire voyage - an exceptional record, given the standards of the day.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"The shorelines and waterways were systematically mapped, but their journals make clear that this reconnaissance called upon a terrible strength in the men who pursued it. Many, boldly led, could not imagine the reason for such hardship; and officers grew weary of trying to impart their visions to reluctant and sullen men." B. Lopez - Arctic Dreams p.359 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Close inspection of some of the journals and papers (including the North Georgia Gazette) relating to Parry’s second Arctic command reveal that not only was he a deeply religious and well-bred officer, but that there was some degree of dissent amongst his officers and crew. Assistant Surgeon Alexander Fisher’s journal states that on 28 February 1820 a portion of the Articles of War was read out in order to maintain discipline.(p.180) Nevertheless, it is interesting to observe that it was under Sir John Barrow’s stewardship of the Admiralty that attention was first paid to the public image of the Royal Navy, particularly with regard to creating the illusion that, in the face of adversity, or in a harsh environment such as the Arctic, discipline was maintained at all times and things were done in the best stiff-upper-lip naval tradition. According to the God-fearing morals of the age, Empire building must be seen to be done in the best British way - even if it meant suppressing some of the realities of the situation, including the true nature of intercourse with the natives, and altering, for purposes of propaganda, the records of voyages and expeditions to be presented to the public. This attitude promulgated in the ‘new era of exploration’ has been maintained by the Navy ever since.

Further, inspired by Barrow's desire for Britain to lead the way in Arctic exploration and the discovery of the fabled 'passage’, after all, it was British exploration that had discovered the openings at each end. But now a new twist was becoming prevalent, even if certain claims proved contradictory, "to shape what one finds to suit one's own ends " a trend that has become all too significant since the beginning of the second millennium.

*Although actually Parry's second voyage into Arctic waters, this voyage has become generally known as Parry's First Voyage.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

References cited or consulted:

Parry, Wm.E., Journal of a Voyage for the Discovery of a North-West Passage, from the Atlantic to the Pacific; preformed in the years 1819-20 in his majesty’s ships Hecla and Griper, under the orders of William Edward Parry RN., F.R.S. and commander of the expedition. With an appendix… John Murray, London 1821.

[W.E. Parry] Letters written during the late voyage of discovery in the Western Arctic Sea. by an officer of the expedition London 1821, Sir Richard Phillips and Co.

Fisher, Alexander. A Journal of a voyage of discovery to the Arctic Regions in His Majesty's Ships Hecla and Griper in the years 1819 & 1820. London Longman et al. 1821.

Parry, Ann. Parry of the Arctic Published by Chatto & Windus, 1963

Sir Richard Phillips and Co. New voyages and travels Vol.5 #5. London 1821.

Lande, L. The Lawrence Lande Collection of Canadiana in the Redpath Library at McGill University - A bibliography. Montreal 1965

Lopez, B. Arctic Dreams C. Scribner's sons, New York 1896.

Sabin J. Bibliotheca Americana, A Dictionary of Books relating to America. New York 1868-1936

Cartographica. Explorers maps of the Canadian Arctic 1818-1860. Monograph No 6. York University, Toronto 1972.

Cooke, Alan & Holland, Clive. The Exploration of Northern Canada 500-1920 A chronology. The Arctic History Press, Toronto 1978

Coleman E.C. The Royal Navy in Polar exploration from Frobisher to Ross

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Relevance of Parry’s First Overall Arctic Command

- This was the first time ships of the Royal Navy had wintered in the Arctic, although whalers had sometimes spent the winter trapped in the ice of Davis Strait. Parry’s meticulous care of his men ensured that all came through safely. The expedition returned home with a mass of scientific data and aroused great popular enthusiasm.

- In Parry’s three major arctic voyages, many problems of northern exploration (health, clothing, boredom in the long winter nights) for winter survival were solved using pioneering techniques.

Among other things, Parry experimented with tinned food, to which he erroneously attributed anti-scorbutic properties, also Mr. Mackintosh’s waterproof canvas, and with Mr. Sylvester’s patent stove, which warmed the ship throughout by means of flues. He taught the men to read and write, and he put on plays for their entertainment.

- Several of the midshipmen who sailed with Parry - notably James Clark Ross, Francis Crozier, and Edward Bird - later became famous explorers themselves, having learnt their skills in “Parry’s School”.

- Alexander Fisher, Assistant Surgeon, made groundbreaking experiments on the specific gravity of ice bergs.

- It was while in their winter quarters that Parry made his famous image of solar light refraction that astounded physicists for many years.

- Cook had melted ice chipped from bergs to replenish water. Parry discovered that pure fresh snow

water could also top-up their water casks a good deal more easily.

- Reinforced the practicality of using heavier built bomb-ketch’s as ice breakers, rather than lighter gun-brigs vessels such as the Griper.

- First time the Beluga Whale song was noted in scientific journals.

- Numerous species of Arctic birds and mammals were recorded.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

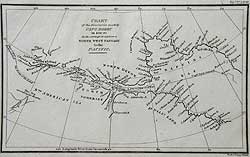

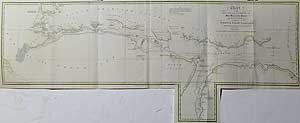

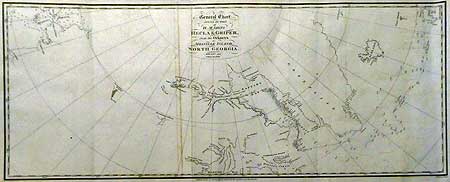

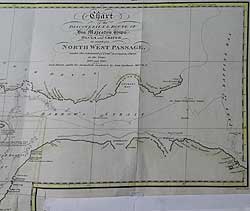

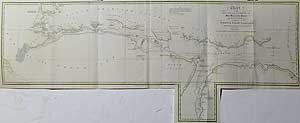

WALKER - Arctic Regions

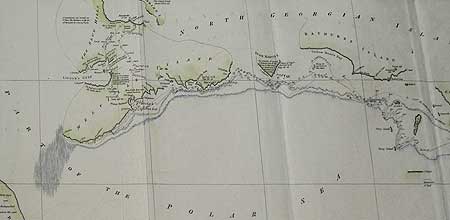

GENERAL CHART shewing the track of H.M. SHIPS HECLA & GRIPER from the Orkneys to MELVILLE ISLAND [sic], NORTH GEORGIA, AD 1819 and return in 1820.

State 1 J. WALKER London 1821

Printed on wove paper. 10 x 24” (25.4 x 60.8 cm.)

Ref. LRA m1083/AN.VL/o.dnsl >ESL

Published in Wm. E. Parry, Journal of a Voyage for the Discovery of a North-West Passage, J. Murray, London 1821, this is the desirable first state of this map. Delineated is British knowledge of the Arctic regions upon the return of Parry's Second Arctic command. This is an important map, as significant advances in the location of certain key landmarks were made between the publication of States I and II or, more precisely, between the return of Parry’s expedition and that of Franklin in 1822. The location of the mouth of the Coppermine River is here shown some 200 miles too far west. This explains why Franklin erected his marker post for Parry at the mouth of the Hood River and not the Coppermine, as Parry's observations would have brought him to that prearranged rendezvous had it been geographically and physically possible.

Also shown are the outward and return tracks of Parry’s voyage, with daily positions, some soundings and notes as to the sea bottom. The position of the sea ice for the outward and return voyages in 1819 and 1820 is located in Davis and Baffin Bays. When Parry departed on his second of five Arctic voyages between 1818 and 1827 [including one to the North Pole] he had with him a Greenland master and mate: a concession to William Scoresby Jnr. whom Palrry had recently met for the first time. Scoresby’s previously unheard knowledge of arctic waters and ice conditions (Barrow had apparently suppressed his own recent correspondence with Scoresby regarding arctic conditions) so impressed Parry that he took the two ex-whalers along as ice navigators.

Parry was instructed to search for Martin Frobisher’s mythical 1578 Sunken land of Buss while making outward passage across the North Atlantic, as had Ross before him. As can be seen from this map no soundings were struck within 175 fathoms of line. In 1791 Captain Charles Duncan, on loan from the Admiralty to the Hudson Bay Company, attempted to locate the mysterious island (title to which had been granted to the H.B.C. in 1675) but had wisely concluded that “no such island is now above water, if it ever was”.

The North Georgia Islands were named for George III but are now known as the Parry Islands. It is from the original name referred to on this map, however, that Parry conceived and named the onboard newspaper the “North Georgia Gazette and Winter Chronicle”.

Vide: Sabine 58860

Cartographica #6, Map 9

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

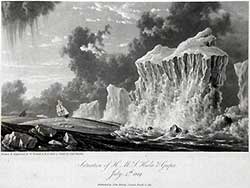

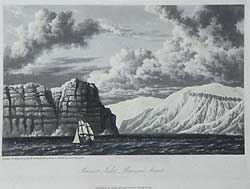

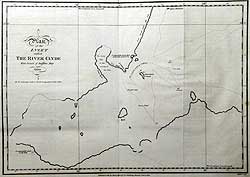

BURNET INLET, BARROW’S STRAIT

6 ¼ x 8” (15.8 x 20.3 cm.) Ref. LRA p9486/RN/da.dose >DNN

This is a hand coloured aquatint, after a sketch by the Lieutenant Hoppner.

4 August 1819, “At noon, being in Latitude 74° 15’ 53”N. Long.86°30’30”, we were near two inlets of which the easternmost was named Burnett Inlet and the other Stratton Inlet. The land between these two have very much the appearance of an island. The cliffs on this part of the coast present a singular appearance, being stratified horizontally and having a number of regular projecting masses of rock, broad at the bottom and coming to a point at the top resembling so many buttresses…[which will be considered] valuable by the geologist and seaman.” Opp.p.34

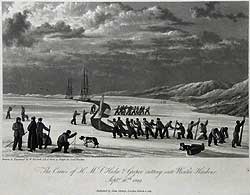

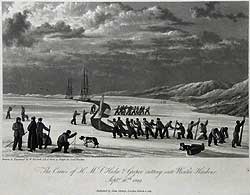

THE CREWS OF H.M.S. HECLA & GRIPER CUTTING INTO WINTER HARBOUR Sept 26th.1819

Size 6 ¼ x 8” (16 x 20.3 cm.) Ref. LRAp Arc2 /DD/e.dosl >DDN

To warp the two ships into a safe anchorage in Winter Harbour, it proved necessary to cut a canal 4,082 yards long through seven-inch-thick ice. Work commenced on 24 September, by marking out two parallel lines the breadth of the ship, then painstakingly cut through the ice with a hand ice saw. The ice was then cut into 10 to 20-foot sections and diagonally cut to be floated along the canal, some by the use of a sail. On the 25th. and 26th. the crew sank the pieces beneath the sides of the canal: "to affect this, it was necessary for a certain number of men to stand upon one end of the piece of ice … while other parties hauling at the same time upon ropes attached to the opposite end dragged the block under that part of the floe on which the people stood…" The officers stood up to their knees in 12°F (-11°C) water; the air temperature was 6°F(-15°C). The canal to the Winter Harbour anchorage was cut through 7” of new ice, the ships were positioned 120 yards apart and 500 feet from the beach.

The entire process is here beautifully depicted as illustrated Opp p. 97

In 1930, a large sandstone rock (Approx. 18ft. x 9.8 ft.)at Winter Harbour marking Parry's 1819 wintering site, was designated a National Historic Site of Canada.

The effects of frostbite on the human body was to prove a significant torment to the crews - toes and fingers being lost. Parry observed and pondered why the Eskimos they met on his previous voyage with Ross (see sect. 10) and also those he met at the river Clyde, seemed not to suffer as much as the Europeans. The secret lay in the layering of native clothing and over his next few commands he learnt a great deal about winter survival clothing from them, particularly in the use of various furs and skins for specific purposes. In 1818/19, he still had much to learn, but he did adapt a loose canvas boot to be fitted with felt lining to give better circulation to the foot, rather than a tight-fitting British leather shoe. Mittens were also issued, but close observation of the majority of the images and reading the journals it would appear that they were not worn as often as one might have expected, with resulting consequences. It was on Parry’s overland expeditions that blankets sewn at the lower end and a draw string at the top to form an early version of a winter sleeping bag, adapted from Eskimo designs, were first employed.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

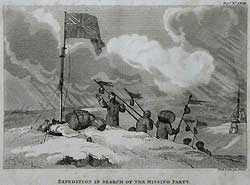

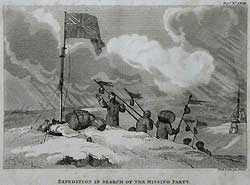

EXPEDITION IN SEARCH OF THE MISSING PARTY

Scarce. NEELE & SON London 1821

3 ¾ x 5 3/8” (9.5 x 13.6 cm.)

Ref LRAp Arc68/DE/ o.dosl> EL

This scarce and expressive engraving depicts an anxious incident during September 1819. On the 10th. Lieutenant Lidden had dispatched a party of seven men from the “Griper” in hopes of killing some reindeer and muskoxen for fresh provisions. Bad weather set in and it was presumed that the party had become lost. On the morning of the 13th. there was still no sign of them, but improved weather conditions enabled four search parties to set out. Lieutenant Hoppner had managed to erect “Hecla’s” fore royal-mast, rigged as a flag staff on a conspicuous hill 4 or 5 miles inland to serve as a beacon and provision depôt the day before. From it the search parties set out, positioning a series of pikes with flags and bottles carrying directional messages attached as markers. This method proved successful and the original party was located, having lived off raw grouse for 91 hours in sub-zero temperatures. Because they lacked adequate arctic survival clothing, exhaustion and frostbite were much in evidence among the seven; nevertheless, all survived the distressing experience. Published in [William E. Parry] Letters written…... Opp.p.44

Realizing how easy it was for crew members to become disorientated in severe winter weather, the ships & shore instrument observation huts were linked by hand lines, a technique still used today.

PREPARING STONES FOR BALLAST

Scarce. NEELE & SON London 1821

3 7/8 x 5 3/8” (9.8 x 13.6 cm.)

Ref LRAp Arc67/AN.vl/ o.dosl> LN

Like the previous image, this was published in [William E. Parry] Letters written during the late voyage of discovery in the Western Arctic Sea. by an officer of the expedition London 1821, Sir Richard Phillips and Co. (#28 Opp p.74.)

With the end of the long winter sojourn almost in sight (the 7th. of February 1820 being the day the members had the first clear view of the sun since November 11th. the previous year). Parry ordered the equipping of the ships for sea. It was reckoned that the “Hecla” would require some 70 tons of ballast plus 20 tons of water to make up for the weight of provisions and stores expended. Stones were therefore brought down the half mile to the beach on sledges, where they were broken into convenient size and weighed on the scales which had been erected, "thus affording to the men a considerable quantity of bodily exercise” Parry

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

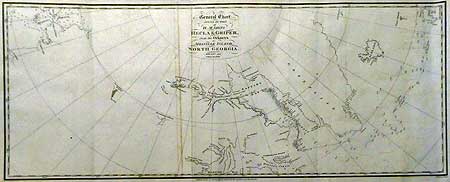

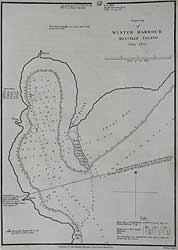

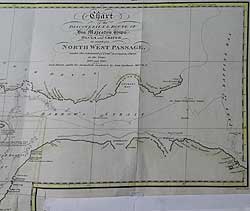

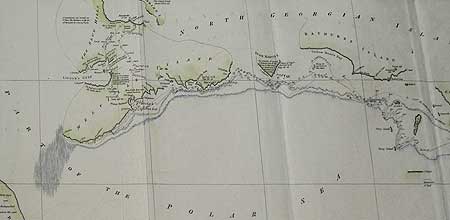

BUSHNAN - North West Passage

CHART of the DISCOVERIES & ROUTE OF HIS MAJESTY’S SHIPS

HECLA and GRIPER in search of a NORTH WEST PASSAGE under the command of Lieut.t (now Captain) Parry in the years 1819 and 1820 and drawn under his immediate inspection by John Bushnan Mid.n RN.

JOHN BUSHNAN. J. Walker. eng. Published J. Murray London 1821

Size 37 ¼ x 9 ½” (94.7 x 24.2 cm.)

On the bottom is a paste-on fold out extension 4 1/2 x 3 15/16” (11.3 x 10 cm.) delineating the coast line of Prince Regents inlet from Port Bowen south to C. Kater with tracks of the ships and extent of the ice.

Delicately hand tinted, printed on watermarked (1818) wove paper.

Ref. LRA 1104/DSL/s.dosl> DALN

Drawn by John Bushnan under Parry’s inspection and engraved by J. Walker it was published in Wm.E. Parry, Journal of a Voyage for the Discovery of a North-West Passage, J. Murray, London 1821. A handsomely hand tinted, good impression of the finest early chart of most of the North West Passage. This highly detailed and elegant chart delineates the outward and return progress of the ships through the ice choked and previously unexplored or charted waters and islands of what was later discovered to be the actual long sought-after passage. Although heavy ice prevented Parry from making the entire passage, this, in the words of Parry’s great, great, granddaughter and biographer “was perhaps the most successful of all Arctic voyages.” Ann Parry Parry of the Arctic 1963

Shown are the ship’s tracks in 1819 & 20 through Barrow’s straight, Prince Regent inlet, Devon, Cornwallis, Bathurst, Byam Martin and Melville Islands, covering a distance of over 30° of longitude. Soundings and observations abound, together with the extent of the sea ice, notes on the sea bed magnetic readings, place names and the aforementioned previously unknown islands. Also, the route of the land party, whilst exploring across Melville Island with detailed observations as to its terrain. The land party were impressed by the abundance of fowl and wildlife, although obtaining enough of the latter to eat proved to be another story. As recorded in Parry’s journal, extricating the two ships from the ice and further progress along the coast of Melville Island proved extremely hazardous. There being no possibility of further progress westward, or opportunity to chart the North American coastline to the south. Being trapped in the ice for another winter became a distinct possibility, which would jeopardize the ship’s stores, the health of the crew (already on 2/3’s bread allowance for 10 months) and possibly the state of the ships. How frustrating it must have been for the questing mind of the young, enthusiastic and ambitious Parry to be almost able to view his goal through the lens of a telescope, but not be able to attain it due to the vagaries of nature. Learning from Ross’s folly of 1818 however, he called for a meeting of his senior officers. It was therefore prudently decided by the officers to turn the ships for home.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|