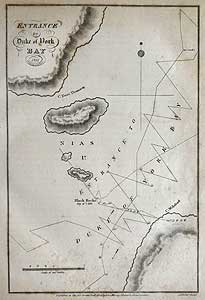

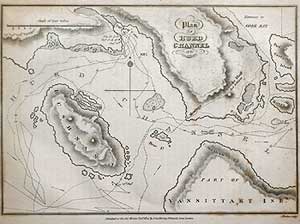

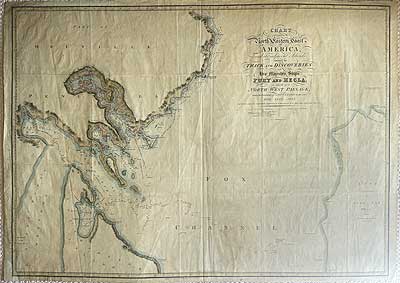

They conducted the first survey of Duke of York Bay, the Frozen Strait and Repulse Bay, confirming Middleton's discoveries of 1742, thus eliminating the last vestige of the bitter controversy. (See section 1)

En route they collected mineral samples such as asbestos, quartz, mica and epidote; continually taking detailed observations of all that they saw of the pristine landscape, with particular attention to the tides. Also mentioned is what is possibly the first European record of an Inukshuk (Parry Vol.IIIp.44)

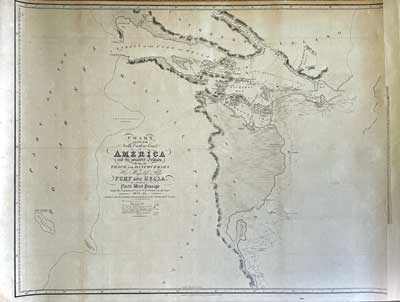

Returning through the Frozen Strait on August 23 via the difficult Hurd Channel, Parry took advantage of the exceptionally mild weather. The ships then commenced the exploration of the Foxe Basin, north of Repulse Bay, along the Melville peninsula, littering the map with explorers graffiti in the names of newly discovered islands, bays, channels and capes including Vansittart Island. During the examination of Lyon Inlet and Ross Bay by ship’s boat and shore parties, field tests of the experimental canvas walled Horseman’s Tent were conducted under arctic conditions, together with a customized sleeping bag.

From the outset of the voyage, serious observation of the ice conditions laid down the rudiments of present day scientific study of the Cryosphere and eventual foundation of the National Snow and Ice Data Centre (NSIDC).

Unlike the more practical Parry, who shouldered the responsibility of overall command, Lyon had great affinity and rare respect for the native Canadian Eskimo. He endeavoured to learn their language, observe and adopt many of the customs of those who lived by the shores of the polar sea. Indeed, he even took native hospitality so far as to father a child. His journal forms an early valuable anthropological thesis of a race as yet untarnished by outside influences.

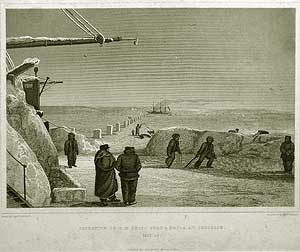

Around the Repulse Bay area, evidence of Eskimo habitation was observed along with numerous Inukshuks, but it was not until Ross Bay that any contact was made. Concluding a minute examination of the coast between Gore Bay and Lyon Inlet, the swift onset of winter caught the ship’s company by surprise and it was only with difficulty that the safe haven of Winter Island was gained. The voyage thus far having added some 200 miles of previously unexplored coast line to the charts.

The ships masts were struck, insulating snow piled high, heating and coverings soon installed to make ready for wintering over. Ample victualling had been provided with enough Donkin and Gamble's Prepared Meats to last until 1824. The experienced officers quickly adopted a routine of work, exercise and artistic pursuit to occupy both body and soul of the crew throughout their long winter sojourn. At last that accomplished violinist William Parry, had now a captive audience for his considerable musical talent, much to the enjoyment of the crew and his own satisfaction. For some it was their first introduction to the music of the Strauss family, Chopin and Mendelssohn. Parry’s violin is now preserved in the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich.

The experience gained on Parry’s previous voyage in wintering-over proved invaluable, for previous experiments in comfort, clothing, entertainment and diet now became almost routine and greatly assisted the well-being and attitude of the ship’s company, for no cases of frostbite or scurvy were yet recorded.

Christmas 1821 was illuminated by brilliant displays of the Aurora Borealis and the New Year by minus l22°F., with a severe wind-chill. On 1st. February 1822 a large number of Eskimo were observed near the ships and their encampment later visited.

Parry may never have known of the Inuit interpretation of his arrival and his activities. But it was clear to the Inuit. He was the realization of Uinigumasuittuq’s prophecy* that her dog-children would return by ship. Despite the language barrier that separated the two races, the Inuit viewed Parry as their kin. This may explain why relations between the Inuit and their Qallunaat visitors remained friendly for most of that winter.