ONE OF THE GREAT APOCRYPHAL MAPS OF THE NORTH ATLANTIC

RUSCELLI /ZENO - North Atlantic Greenland & Scandinavia

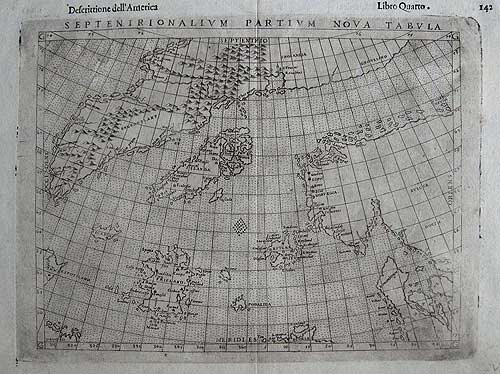

SEPTENTRIONALIUM PARTIUM NOVA TABULA

Girolamo Ruscelli. Venice [1561(1599)]

Original copper- engraved map uncoloured as issued. Map: 7 x 9 3/8 " (17.8 x 23.8 cm.) plate size 7 3/8 x 10 1/4 (18.5 x 26 cm.) From Book 4 Descrittione dell'America p.142 Italian text on verso.

Ref. DGL m827 /ALN/r.dosa >DGLN PRICE CODE F

Full Title

Septentrionalivm Partivm nova tabvla. Published in Descrittione dell'America. Libro Quarto. (to accompany) La Geographia di Clavdio Tolomeo alessandrino, tradotta di Greco nell'idioma volgare Italiano da Girolamo Ruscelli ... In Venetia, MDXCIX (1599) Appresso gli heredi di M. Sessa.

On verso: "De' Paesi Settentrionali Tavola Nvova"; In upper left margin: Descrittione dell' America; In upper right margin: Libro Quarto: 142.; Title at top outside neat line "Septenirionalivm Partivm Nova Tabvla"".; Based upon Gastaldi's miniature map of 1548.

The Map

An elegantly engraved map, with the sea in typical Ruscelli stippled manner, depicting Greenland (without its apocryphal canals) and the North Atlantic. Iceland is central to the map. One of the most significant maps in Girolamo Ruscelli's edition of Ptolemy's Geographia atlas is his Septentrionalium Partium Nova Tabula map, is based upon the Zeno map of the North Atlantic, which was first included in a 1558 travel book, and describes a pre-Columbian voyage to the New World in 1380 by Ventians Nicolo and Antonio Zeno. It is considered to be one of the Most Captivating and intriguing Maps in the History of Cartography.

The map introduces many new fictitious islands in great detail, including Frisland (with 32 places named), Deogeo, Estotiland, Estland, Podalida and Icaria and the monastery of St. Tomas in Greenland, all taken from the notorious Zeno map of reputed voyages in the 14th century. Many of these mythical islands and places were depicted on maps for centuries, mainly because Gerard Mercator accepted Zeno's voyage as authentic and adopted much of it in his famous large 1569 world map and his 1595 map of the North Pole. Ortelius in turn, used the map as a prototype for his map of the North Atlantic. Frobisher and Davis accepted the map for their explorations in the 1570's and 1580's, respectively.

The Zeno brothers and their voyage of 1380

The Zeno family was part of the Venetian elite; indeed, their family had controlled the monopoly over transport between Venice and the Holy Land during the Crusades. Nicolo Zeno set off in 1380 to England and Flanders; other evidence seems to corroborate this part of the voyage. Then, his ship was caught in a huge storm, blowing him off course and depositing him in the far North Atlantic. He and his crew were wrecked on a foreign shore, the island of Frislanda.

Thankfully, the shipwrecked Venetians were found by King of Frisland, Lord Zichmi, who also ruled Porlanda, an island just south of Frisland. Zichmi was on a crusade to conquer his neighbors and Nicolo was happy to help him strategize. Nicolo wrote to his brother, Antonio, encouraging him to join him and, good navigator that he was, Antonio sailed for Frisland and arrived to help his brother. Together, they led military campaigns against Zichmi's enemies for fourteen years. Lord Zichmi was believed by Captn. Cook's sailing companion, Johann Forster (in 1784) to be Henry Sinclair, Earl of Orkney.

Their fights led the brothers to the surrounding islands, presumably enabling them to make their famous map. Zichmi attempted to take Islanda, but was rebuffed. Instead, he took the small islands to the east, which are labeled on this map. Zichmi built a fort on one of the islands, Bres, and he gave command of this stronghold to Nicolo. The latter did not stay long, instead sailing to Greenland, where he came upon St. Thomas, who founed a monastery in Greenland with central heating. This too is marked on the map. Nicolo then returned to Frisland, where he died four years later, never to return to Venice.

Antonio, however, was still alive. His letter explains that he ran into a group of fishermen while on Frisland. These fisherman had been on a 25 year sojourn to Estotiland, which is peeking out of the western border of the map. Supposedly, Estotiland was a great civilization and Latin-speaking, while nearby Drogeo, to the south, was full of cannibals and beasts. Antonio, on Zichmi's orders, sought these new lands, only to discover Icaria instead. The Icarians were not amenable to invasion, however, and Antonio led his men north to Engroneland, to the north. Zichmi was enthralled with this new place and explored inland. Antonio, however, returned to Frisland, abandoning the King. From there, Antonio sailed for his native Venice, where he died around 1403.

Publication and legacy

News of the discoveries and the first version of this map was published in 1558 by another Nicolo Zeno, a descendent of the navigator brothers. Nicolo the Younger published letters he had found in his family holdings, one from Nicolo to Antonio and another from Antonio to their other brother, Carlo, who served with distinction in the Venetian Navy. They were published under the title Dello Scoprimento dell'isole Frislanda, Eslanda, Engrouelanda, Estotilanda, & Icaria, fatto sotto il Polo Artico, da due Fratelli Zeni (On the Discovery of the Island of Frisland, Eslanda, Engroenland, Estotiland & Icaria, made by two Zen Brothers under the Arctic Pole) (Venice: Francesco Marcolini, 1558).

At the time of publication, the account attracted little to no suspicion; it was no more and no less fantastic than most other voyage and travel accounts of the time. Girolamo Ruscelli (ca. 1504-1566) published this version of the Zeno map in 1561, only three years after it appeared in Zeno's original work. Ruscelli was a Venetian publisher who also released an Italian translation of Ptolemy. Ruscelli had moved to Venice in 1549, where he became a prominent editor of travel writings and geography.

Ruscelli was not the only geographer to integrate the Zeno map into his work. Mercator used the map as a source for his 1569 world map and his later map of the North Pole. Ortelius used the Zeno islands in his map of the North Atlantic. Ramusio included them in his Delle Navigationo (1583), as did Hakluyt in his Divers Voyages (1582) and Principal Navigations (1600), and Purchas (with some reservation) in his Pilgrimes (1625). Frisland appeared on regional maps of the North Atlantic until the eighteenth century.

In the nineteenth century, when geography was popular as both a hobby and a scholarly discipline, the Zeno account and map came under scrutiny. Most famously, Frederick W. Lucas questioned the validity of the voyage in The Annals of the Voyages of the Brothers Nicolo and Antonio Zeno in the North Atlantic (1898). Lucas accused Nicolo the Younger of making the map up, using islands found on other maps and simply scattering them across the North Atlantic. He also accused Nicolo of trying to fabricate a Ventian claim to the New World that superseded the Genoan Columbus' voyage. Other research has revealed that, when he was supposed to be fighting for Zichmi, Nicolo was in the service of Venice in Greece and Venice in the 1390s. He is known to have drafted a will in 1400 and died-in Venice, not Frisland-in 1402.

Scholars still enjoy trying to assign the Zeno islands to real geographic features. For example, Frisland is thought to be part of Iceland, while Esland is supposed to be the Shetlands; Deogeo part of North America, and the unknown land mentioned in the book, possibly Nova Scotia (nr. Stellarton) or Newfoundland (nr. Port de Grasse) There is no doubt however that the map and tale was the inspiration for Martin Frobisher's 1576 voyage. Some still believe the Zenos to have sailed to these lands. Most, however, view the voyage and the map as a reminder of the folly and fancy (and fun) of early travel literature and cartography. Whatever the truth, the Zeno map and its islands are one of the most enduring mysteries in the history of cartography and the Ruscelli map sped the story's exposure in Europe.

Tooley, revised edition Q-Z, 87. Edward Brooke-Hitching, The Phantom Atlas: The Greatest Myths, Lies and Blunders on Maps (London: Simon & Schuster, 2016), 242-4.

For an example of one who believes in the Zeno map, see William Herbert Hobbs, “Zeno and the Cartography of Greenland,” Imago Mundi VI (1949): 15-19.

Claudius Ptolemy (90-168 CE) was a Roman geographer and mathematician living in Egypt, who compiled his knowledge and theories about the world's geography into one seminal work. Although his maps did not survive, his mathematical projections and location coordinates did.

Girolamo Ruscelli (c. 1504-1566) was a Venetian editor, whose maps are primarily based on those by Jacopo Gastaldi (1548) but with many of his own additions and reproduced on a larger scale.

Back

Home | Contact | Location | Links | Antique Prints | Fine Art | Antique Maps | Omnium Gatherum | Specialty Services